Abstract:

In a market that is becoming increasingly competitive, the proactive behaviors demonstrated by employees have become a key element for organizations. Therefore, this study focuses on the mechanism of leadership affinity humor on employee proactive behavior and introduces supervisor emotional commitment as a mediating variable to construct a theoretical model on the interaction among them. In order to verify the validity of this model, we used the questionnaire method to collect data, and used SPSS 27.0 and AMOS 28.0 to analyze the data and test the model. The results showed that leaders' affinity humor significantly promoted employees' proactive behaviors, while supervisors' emotional commitment played a mediating role in this process. This finding not only enriches the theoretical research on the influence of leaders' affinity humor on employees' proactive behaviors in the Chinese context, but also helps companies to better understand the formation mechanism of employees' proactive behaviors, and then propose more accurate and effective management strategies to motivate employees to display more proactive behaviors. Canada’s workplace

culture places a strong emphasis on leadership behaviors that foster trust, engagement, and innovation and the article will also share some insights from Canada’s practice.

Keywords:

Leadership affinity humor ;supervisor's emotional commitment;employee proactive behavior

1 Introduction

1.1 Research Background

In recent years, under the new normal of economic development, enterprises face increasingly complex growth environments. The intensification of globalization has escalated competition among domestic and international enterprises, while rising uncertainty presents unprecedented challenges for corporate management. In Canada, this challenge is particularly notable as the country grapples with both regional economic disparities and the need to adapt to global trade agreements, such as the Canada-United States-Mexico Agreement (CUSMA). Canadian businesses must navigate this dynamic landscape while fostering a competitive edge. Against this backdrop, humor, as a unique form of communication, stands out for its ability to facilitate interpersonal interactions by reducing barriers and fostering closer connections. Leaders' sense of humor has emerged as an effective management tool, especially in organizational activities. Successful leaders in Canadian organizations, for instance, often use humor to motivate employees,

garner their trust and support, and, when appropriately incorporated into serious management contexts, ease tension and naturally inspire employees' proactiveness and enthusiasm.

This study aims to explore the relationship between affiliative humor exhibited by leaders and proactive employee behavior. It incorporates emotional commitment as a mediating variable to provide a comprehensive understanding of the mechanisms through which affiliative humor functions, thereby

enhancing proactive behavior in employees. This study also aims to offer new insights and strategies for corporate employee management to effectively promote proactive behaviors.

1.2 Research Objectives and Significance

1.2.1 Research Objectives

This study focuses on proactive employee behavior, delving into the potential relationship between leaders’ affiliative humor and employees' proactive behaviors. It also examines the importance of emotional commitment as a critical emotional factor in interpersonal interactions .

Specifically, the study investigates the mediating role of employees’ emotional commitment in the relationship between affiliative humor and proactive behavior.

1.2.2 Research Significance

Theoretical Significance

In the context of Chinese culture, this study not only highlights the importance of employees' emotional commitment but also deepens the understanding of the interaction mechanism between leadership humor styles and

proactive employee behavior. By thoroughly investigating this mediating variable, the research provides a robust theoretical foundation for improving organizational effectiveness.

Practical Significance

The affiliative humor displayed by leaders has significant predictive value for

proactive employee behavior. Organizations should recognize the importance of cultivating this humor style among leaders to effectively enhance employees’ proactiveness.

Management Significance

Companies should also pay attention to employees’ emotional commitment toward their supervisors, a key factor influencing employees’ work

attitudes and behaviors. By valuing emotional commitment, enterprises can gain deeper insights into employees' mindsets and implement more effective management measures.

1.3 Research Methods and Structure

1.3.1 Research Methods

This study employs the following research methods:

Literature Review

During the preparatory phase, the study identified "humor" as the focal leadership behavior. A comprehensive literature review was conducted to explore the potential

relationships among affiliative humor, proactive employee behavior, and emotional commitment. The review clarified core research topics, variables, and their dimensions

and measurement methods. Based on established theories, research hypotheses were formulated, laying a solid foundation for empirical investigations.

Survey Method

Questionnaires were designed using validated scales, with precise translations and optimizations.

Surveys were distributed online to employees in Chongqing and Sichuan. Data quality was ensured through appropriate adjustments,

providing reliable support for the research.

Statistical Analysis

Data collected were analyzed using software such as SPSS 27.0 and AMOS 28.0. Regression analysis was employed

to test the validity of the hypotheses, supplemented by bootstrap methods for robustness checks. Results from these analyses were synthesized for a comprehensive understanding.

1.3.2 Thesis Structure

1: Introduction

This chapter outlines the research background and the central theme, clarifying the research objectives and exploring the theoretical and

practical significance of the topic.

2: Literature Review

A systematic review of core variables, including affiliative humor,

emotional commitment, and proactive employee behavior, is provided. This review forms the theoretical basis for model construction and hypothesis testing.

3: Model Construction and Hypotheses

Based on previous studies,

the core research model is constructed. The chapter details the logic and rationale behind the model and hypothesis development, providing a clear framework

for empirical analysis.

4: Measurement and Sample Analysis

This chapter

focuses on measurement methods for the three key variables and presents a detailed descriptive statistical analysis of the sample, including validity

and reliability assessments.

5: Data Analysis and Model Testing

The chapter describes the survey sample and its distribution, followed by reliability analysis using SPSS 27.0.

Regression analysis is performed to examine the relationships between variables, and hypotheses are empirically tested for robust conclusions.

6: Conclusions and Future Directions

This chapter summarizes the empirical findings,

highlights key conclusions, and offers managerial recommendations. It also discusses limitations and suggests future research directions to inform subsequent studies.

2 Literature review

2.1 Affiliative Humor of Leaders

2 .1.1 Definition ofAffiliative Humor in Leadership

As a catalyst for interpersonal relationships, leadership humor plays a role in social adjustment in the workplace. Freud's traditional theory suggests that humor is an external manifestation of the subconscious. Western academic research on leadership humor can be traced back to the late 20th century. Current studies focus on two main perspectives: behavior- oriented and trait-oriented, providing an in-depth understanding of leadership humor. From the behavioral perspective, leadership humor is seen as a deliberate act of social communication in which managers intentionally evoke positive emotions in

subordinates to create a pleasant environment (Cooper, et al.,2018). From the trait perspective, humor is regarded as an innate or acquired personality trait of leaders.

Among the four types of humor (Martin , et al.,2003), affiliative humor involves the use of friendly humor (e.g., banter or jokes) to amuse others,

thereby fostering social interactions with employees, reducing interpersonal tension, and creating a positive work atmosphere.

2 .1.2 Dimensions and Measurement ofAffiliative Humor in Leadership

Measurement tools for humor are predominantly developed in Western contexts. Martin’s affiliative humor scale is widely recognized and employed in academic research. Pundt later adapted this scale to suit different research scenarios (Pundt A.,2015). Building on Martin's work,

Chinese scholar Shi Guanfeng et al.developed a Chinese version of the affiliative humor scale tailored for workplace studies, comprising six items( Shi Guanfeng et al.,2018).

Based on a review of the literature, this study adopts the six-item scaleby Shi et al.,

which has demonstrated high reliability and validity in domestic studies on leadership humor (Shi Guanfeng et al.,2018).

2 .1.3 Relevant Research on Affiliative Humor in Leadership

(1) Influencing Factors ofAffiliative Humor in Leadership

Research on the antecedents of affiliative humor in leadership is limited, with most studies treating leadership humor as a whole. From a gender perspective, Decker found that female executives generally use humor more frequently than their male counterparts, who are more inclined to use negative humor styles (Decker,2015). In terms of job performance, Priest and Swain’s empirical research revealed that highly effective and outstanding leaders tend to exhibit positive humor traits(Priest et al.,2016 ). However, research on the relationship between leadership–member

exchange (LMX) and affiliative humor has yielded inconsistent findings. Pundt and Herrmann suggested a positive correlation between LMX and affiliative humor (Pundt A et al.,2015).

(2) Outcomes ofAffiliative Humor in Leadership

Studies on the outcomes of affiliative humor in leadership focus on both individual and team levels. On an individual level, numerous studies indicate that affiliative humor significantly enhances employees' innovation capabilities and improves communication between management and subordinates (Pundt A et al.,2015). Additionally, research by Kim et al.

revealed that both affiliative and self-enhancing humor positively impact employees' mental health, whereas aggressive humor negatively affects it (Kim, T. Y et al.,2016).

On a team level, Gao Jie et al. demonstrated that affiliative humor fosters positive LMX relationships, which in turn

promote internal team learning (Gao Jie et al.,2019). Wang Rongrong et al. found that affiliative humor positively correlates with team effectiveness, with LMX serving as a mediating factor (Wang Rongrong et al.,2021).

In conclusion, while considerable research highlights the positive effects of affiliative humor, insufficient attention has been paid to its antecedents.

2 .2 Proactive Employee Behavior

2 .2 .1 Definition of Proactive Behavior

Proactive behavior refers to employees taking initiative to improve their circumstances or the organization by assuming challenges, overcoming obstacles,

and achieving goals. It emphasizes self-driven and forward-thinking actions, such as redefining tasks, actively seeking feedback, and seizing opportunities (Crant, J. M.,2000).

First proposed by Bateman in 1993, proactive behavior is characterized as an active process that transcends norms, asserts control, and promotes agency over passive responses. Employees exhibiting proactive behavior set challenging goals and actively seek to innovate or improve their environments based on their capabilities.

Bateman et al. later enriched the concept, describing proactive behavior as actively shaping desired outcomes by not only predicting but also creating change.

Early research centered on individual characteristics (e.g., proactive personality) and job traits (e.g., autonomy) as mechanisms for proactive behavior (Ohly, S. et al.,2017) (Marinova, S. V.et al.,2015). However, given the increasing interdependence in the workplace, researchers have shifted toward exploring the role of social contexts, particularly leadership behavior, in fostering proactive

behavior (Cai, Z. et al.,2019). While existing studies emphasize the "ability" of leaders to support employees' proactive behavior, few delve into the "willingness" aspect.

2 .2 .2 Antecedents ofProactive Employee Behavior

Research on antecedents of proactive behavior focuses on individual and contextual factors. Individual factors include demographics like age and gender. For instance, while some studies report a negative correlation between age and proactive behavior, others find no significant predictive effect (Matsuo, M., 2022).

Gender studies reveal that men tend to demonstrate higher proactive tendencies in areas like job-seeking and networking compared to women (Wu, X. et al.,2018).

Contextual factors such as task characteristics and team climate have been widely studied (Kim, S., & Ishikawa,

J.,2021) (Meyers, M. C.,2020), though other potential influencing factors remain underexplored. The interaction between individual and contextual factors also impacts proactive behavior(Xu, Q. et al.,2019). For example, employees with proactive personalities are more likely to exhibit proactive behaviors in environments that emphasize fairness or provide positive feedback (Zhang Ying et al.,2022). Additionally, workplace

gossip can significantly influence proactive behavior; negative gossip often leads to distrust and reduced positivity, diminishing proactive tendencies (Du Hengbo et al.,2019).

2 .2 .3 Measurement ofProactive Employee Behavior

Research on measuring proactive behavior often employs Likert scales for self-reports. Prior to the formal conceptualization of proactive behavior, proactive personality scales were widely used to assess individual tendencies toward proactivity (Parker, S. K., et al.,2006). Frese et al. later developed a single-dimension scale tailored to capture proactive behaviors more precisely (1997). Morrison and Phelps (1999) designed a scale to assess behaviors contributing to organizational development,

but it lacked focus on self-improvement. Parker et al. developed a seven-item scale integrating interviews and surveys, which has gained wide application (Frese, M., et al.,1997).

This study employs Frese, Fay, and Hilburger’s (1997)

single-dimension scale comprising seven items to comprehensively assess proactive employee behavior (Clugston, M. et al.,2000).

2.3 Affective Commitment of Employees

2 .3.1 Concept ofAffective Commitment

Building on organizational commitment theories, researchers have gradually recognized that employees' commitments extend beyond the organization to include diverse targets. Clugston et al. (2000) noted similarities between supervisory and organizational commitment, reflecting psychological dependence and

attachment to supervisors (Zhao, H. et al.,2016). Affective commitment, defined as emotional attachment, identification, and involvement with a specific target, has become a

central focus due to its predictive power regarding employee behavior.

In the Chinese cultural context, individuals often exhibit deeper responsibility and obligation toward closely related individuals, making affective commitment particularly relevant for understanding employee motivation (Landry, G., & Vandenberghe, C.,2009). Drawing on Landry et al., this study defines affective commitment as subordinates' emotional attachment

and identification with supervisors, highlighting the importance of high-quality work relationships in improving organizational effectiveness (O'Reilly, C. A., & Chatman, J.,1986).

2 .3.2 Dimensions and Measurement ofAffective Commitment

Several mature tools are available to measure affective commitment. Based on attitude change theories, O'Reilly and Chatman (1986) categorized organizational commitment into compliance, identification, and internalization (Becker, T. E., (1992). Becker (1992) adapted this scale by replacing "organization" with "supervisor" and adding five items to create a 17- item supervisory commitment scale (Becker, T. E.et al.,1996). Allen and Meyer’s (1990) three-dimensional organizational commitment framework led to a widely adopted scale (Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P.,1990).

Later, Vandenberghe et al. (2004) refined this scale to focus on supervisors, selecting five items that best reflected affective commitment (Vandenberghe, C. et al.,2004).

For this study, we use Meyer and Allen’s (1990) authoritative scale,

validated for use in China. A five-point Likert scale is employed, where higher scores indicate stronger affective commitment (Wang, Y. Q.,2012).

2 .3.3 Relevant Research on Affective Commitment

Research on affective commitment is organized into antecedents and outcomes. Antecedents include cultural factors, LMX, and perceived organizational support. Clugston et al. (2000) emphasized collectivism’s role in supervisory commitment (Zhao, H., & Long, L.,2016). Stinglhamber et al. (2003) found that perceived supervisor support positively impacts affective commitment (Stinglhamber et al.,2003).

Domestic studies have further revealed the mediating role of affective commitment between organizational support and employee behaviors (Yan, J.et al., 2016) (Baek, H.,2019).

Outcomes of affective commitment include job performance, organizational citizenship behavior,

and turnover intentions. Askew et al. (2013) highlighted significant correlations between supervisory affective commitment and these variables (Askew, K.et al.,2004)

In summary, while extensive research has been conducted on organizational commitment, studies on supervisory commitment,

particularly affective commitment, remain limited. Future research should explore the connections between affiliative humor, proactive behavior, and affective commitment.

3 Model Development and Research Hypotheses

3.1 Problem Statement

Employees' proactive behavior is indispensable to the growth and prosperity of organizations. Despite early studies in this domain, the topic continues to attract the interest of managers, underscoring its enduring research value. Currently, many Chinese scholars explore the impact of Western leadership styles on Chinese employees' proactive behavior. However, given cultural differences between East and West, directly applying Western leadership models to Chinese enterprises may face adaptability issues. Moreover, the relationship between affiliative humor in leadership and employees' proactive behavior remains inconclusive, providing ample scope for further research. Lastly, prior studies have paid insufficient attention to the pivotal role of employees' affective commitment in the relationship between affiliative humor and proactive behavior, leaving the underlying mechanisms inadequately explained. Based on these considerations, this study identifies affiliative humor in leadership as a critical factor influencing employees'

proactive behavior. It introduces employees' affective commitment as a mediating variable to explore the internal mechanisms between affiliative humor and proactive behavior.

3.2 Hypothesis on the Impact of Affiliative Humor in Leadership on Employees' Proactive Behavior

Affiliative humor exhibited by leaders significantly influences employees' work engagement and performance and effectively motivates them to undertake more extra-role behaviors. When employees perceive affiliative humor from their leaders,

the work environment becomes more positive, open, and inclusive. This fosters a sense of personal care and harmonious

communication between leaders and subordinates. Under such conditions, employees experience enhanced autonomy, sustained vitality in their work,

enthusiasm for contributing to the organization, and a maintained sense of novelty and creativity in their tasks.

Employees interpret affiliative humor as a signal of approachability, leading them to feel that their leaders genuinely care for them. This recognition not only acknowledges their work but also strengthens the emotional bond between leaders and employees, enhancing their sense of belonging(Wu, C. H., & Parker, S. K.,2017). Furthermore, affiliative humor from leaders can evoke employees’ sense of role obligation and feelings of gratitude and reciprocity. Based on agency theory, affiliative humor fosters employees’ gratitude and

willingness to reciprocate toward both the leader personally and the organization as a whole, encouraging them to exhibit more positive behaviors (Zhao, H., & Long, L.,2016).

These findings suggest that leaders’ behavior significantly affects employees’ attitudes and emotional responses toward them. When these attitudes and emotions are positive,

employees tend to translate their favorable reactions to leaders into constructive workplace behaviors. Accordingly, this study proposes the following hypothesis:

H1: Affiliative humor in leadership positively predicts employees' proactive behavior.

3.3 Hypothesis on the Impact of Affiliative Humor in Leadership on Employees' Affective Commitment

When employees hold favorable attitudes toward their supervisors' behavior or achievements, they exhibit higher levels of affective commitment to their supervisors. This process reflects the emotional bond between employees and leaders and reveals the

psychological motivation underlying employees’ behavior. In response to the personalized care provided by leaders, subordinates often enhance their identification with the leaders.

In corporate management, differences in employees' perceptions form a differentiated structure, which profoundly influences organizational behavior in Chinese contexts (Zheng, B. X.,2006). Leaders, as authoritative representatives within organizations, often convey "in-group" signals through affiliative humor. Consequently, affiliative humor fosters strong emotional bonds between leaders and their "in-group" members, characterized by mutual trust

and attraction, and enhances employees’ perception of belonging to the inner circle (Stamper, C. L., & Masterson, S. S.,2002). Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H2: Affiliative humor in leadership positively predicts employees' affective commitment.

3.4 Hypothesis on the Impact of Employees' Affective Commitment on Proactive Behavior

Controlling for demographic variables and organizational commitment, employees' affective commitment toward their supervisors can effectively predict their proactive behavior (Zhao, H., & Long, L.,2016). In the unique social context of China, the power distance between superiors and subordinates tends to be relatively large. Supervisors, compared to organizations as a whole, are more likely to become the emotional anchors for employees. Employees establish closer emotional ties with their supervisors and are consequently more inclined to proactively

undertake work responsibilities, thereby increasing the likelihood of proactive behavior (Wu, C. H., & Parker, S. K.,2017). Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H3: Employees' affective commitment positively predicts proactive behavior.

3.5 Mediating Role of Affective Commitment

Affiliative humor exhibited by leaders creates a positive and harmonious communication atmosphere and an amicable organizational environment. This atmosphere effectively stimulates employees' positive emotions, bringing vitality to the organization, fostering

deeper affective commitment toward the leader, and increasing the likelihood of employees exhibiting proactive behavior. Based on this, the following hypothesis is proposed:

H4: Affective commitment mediates the relationship between affiliative humor and proactive behavior.

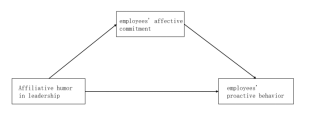

3.6 Conceptual Model

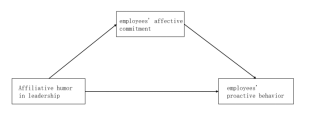

Based on the above theoretical reasoning, this study proposes four hypotheses, which are presented as follows.

Table3.1 Assumes Summary

Hypotheses

H1 Affiliative humor in leadership positively predicts employees' proactive behavior.

H2 Affiliative humor positively predicts employees' affective commitment.

H3 Employees' affective commitment positively predicts their proactive behavior.

H4 Employees' affective commitment mediates the relationship between affiliative humor and proactive behavior.

Based on the detailed discussion and hypothesis analysis presented earlier,

the following theoretical model (Figure 3.1) is constructed to clearly illustrate the research framework and expected outcomes.

Figure 3.1 Theoretical Model

4 Questionnaire Design and Measurement

4.1 Questionnaire Design

This study employed a questionnaire survey method to collect data. The detailed steps areas follows:

Determination of Measurement Scales: During the initial questionnaire design phase, a comprehensive review of domestic and international literature on leadership-friendly humor,

employees’ emotional commitment, and proactive behavior was conducted. Widely accepted and frequently used established scales were selected.

Translation of Scales: When translating commonly used foreign research scales, careful translation and

revisions were carried out, leveraging the extensive experience of domestic researchers. Ambiguous items were refined and improved.

Final Integration of the Questionnaire: The questionnaire content included the research purpose, basic information about the respondents, and the selected scales.

4.2 Variable Measurement

The variables in this study include leadership-friendly humor, employees’ emotional commitment, and proactive behavior. Data were collected using a 5-point Likert scale, where “1” indicates “strongly disagree,” and “5” indicates “strongly agree.” After selection and confirmation,

the final items for each scale were as follows: leadership-friendly humor (8 items), employees’ emotional commitment (8 items), and proactive behavior (7 items).

4.2 .1 Measurement Scale for Leadership-Friendly Humor

The study relied on first-hand data obtained through questionnaires and conducted empirical analysis.

The measurement scale developed by Shi Guan-feng et al. (2017) [4], widely used in relevant research, was adopted. The items of the scale are shown in Table 4.1:

Table 4.1 Leadership-Friendly Humor Measurement Scale

Variable Item Descriptions

Leadership-Friendly Humor 1. My supervisor rarely jokes with others.

2. My supervisor easily makes others laugh and seems to be naturally humorous.

3. My supervisor seldom tells amusing stories about themselves to make others laugh.

4. My supervisor frequently jokes with their closest friends.

5. My supervisor usually does not enjoy telling jokes or amusing others.

6. My supervisor likes making others laugh.

7. My supervisor rarely jokes with their friends.

8. My supervisor usually cannot come up with witty remarks when with others.

4.2 .2 Measurement Scale for Employees ’ Emotional Commitment

This study employed a widely recognized scale validated by Meyer and Allen (1991) [46], which has been shown to be suitable for China’s context.

Eight items were selected for analysis, using a 5-point Likert scale to measure the level of employees’ emotional commitment.

Table 4.2 Employees’ Emotional Commitment Measurement Scale

Variable Item Descriptions

Employees’

Emotional Commitment 1. Iam happy to spend my career at this company.

2. Iam willing to talk about my company with people outside the organization.

3. I consider the company’s problems as my own.

4. It would be difficult forme to feel as attached to another company as Ido to this one.

5. I feel like apart ofthe “family” at this company.

6. I have an emotional attachment to this company.

7. I have a strong sense of belonging to this company.

8. This company means a great deal tome.

4.2.3 Measurement Scale for Employees’ Proactive Behavior

This study utilized the Proactive Behavior Scale developed by Frese, Fay, and Hilburger (1997) [24]. The scale is unidimensional and includes seven items.

Table 4.3 Employees’ Proactive Behavior Measurement Scale

Variable Item Descriptions

Employees’ Proactive Behavior 1. I actively solve problems.

2. Whenever Iencounter a problem, I immediately seek solutions.

3. Whenever there is an opportunity to participate in work activities, I seize it.

4. I take immediate action, even if others do not.

5. To achieve my goals, I quickly seize opportunities.

6. Generally, Ido more than what is required.

7. I excel at bringing my ideas to life.

5 Data Analysis and Model Testing

5.1 Overview of Survey Samples

5.1.1 Distribution and Collection of Questionnaires

During the design of the questionnaire, the names of all variables were hidden, and only the items were displayed to prevent respondents from intentionally providing inaccurate answers due to

self-presentation bias or self-protection motives. Additionally, positive and reverse-coded items were presented in a randomized order to minimize response bias caused by inertia.

The data collection period for this study spanned from January to April 2024, targeting private enterprises, foreign- funded enterprises, joint ventures, and other organizations in regions such as Chongqing and Chengdu. Initially, a pilot survey was conducted to test the scientific validity and comprehensibility of the questionnaire items. Necessary revisions

were made based on the feedback received. Subsequently, the finalized electronic questionnaire was distributed through online platforms to ensure data accuracy and breadth.

A total of 390 questionnaires were collected. After a rigorous data-cleaning process, invalid questionnaires,

including those with incomplete or careless responses, were excluded. This resulted in 301 valid responses, yielding an effective response rate of 77.2%.

5.1.2 Descriptive Statistics of the Sample

The 301 valid questionnaires included basic information about respondents, such as gender, educational background, age,

and the duration of collaboration with their current supervisors. Descriptive statistics from this data are presented in Table 5.1.

Key observations from Table 5.1:

Gender: Males accounted for 41.2% of the sample, while females comprised 58.8%.

Educational Background: Undergraduate and postgraduate (or higher) respondents constituted 77% of the sample.

Age: Respondents aged 25 years or younger represented 44.2% of the sample, and those aged 26–30 comprised 27.2%, collectively accounting for 71.4%.

Duration of Collaboration with Current Supervisors: Employees who had worked with their current supervisors for 0–4 years represented 72.1% of the sample.

Table 5.1 Descriptive Statistics of the Sample

Variable Level Number Percentage (%)

Gender Male 124 41.2%

Female 177 58.8%

Education HighSchool/Vocational 21 7.0%

College Diploma 48 15.9%

Undergraduate 153 50.8%

Postgraduate 79 26.2%

25 years or younger 133 44.2%

26–30 years 82 27.2%

Age 31–35 years 45 15.0%

36–40 years 18 6.0%

Over 41 years 23 7.6%

2 years or less 149 49.5%

Collaboration Duration 2–4 years 68 22.6%

4–6 years 50 16.6%

Over 6 years 34 11.3%

5.3 Reliability and Validity Analysis of Scales

In this section, the reliability and validity of the scales for key variables,

including leadership-friendly humor, employees’ emotional commitment, and proactive behavior, were analyzed to evaluate the robustness of the questionnaire.

5.2 .1 Reliability Analysis

Reliability assesses the consistency and dependability of responses. Cronbach’s α coefficient was used as the reliability indicator. Generally, higher α values indicate better

reliability and internal consistency of the data. Values exceeding 0.8 indicate excellent reliability, while those above 0.7 are acceptable.

The Cronbach’s α coefficients for leadership-friendly humor, employees’ emotional commitment, and proactive behavior were calculated, as shown in Table 5.2:

Table 5.2 Reliability Analysis of Scales

Measurement Variable Number of Items Cronbach’s α Coefficient

Leadership-Friendly Humor 8 0.940

Employees’ Emotional Commitment 8 0.930

Proactive Behavior 7 0.887

From Table 5.2, all variables exhibit Cronbach’s α coefficients above 0.8,

demonstrating outstanding reliability and internal consistency. Hence, the collected data passed the reliability test and can be deemed stable and dependable.

5.2 .2 Validity Analysis

(1) Validity Analysis ofLeadership-Friendly Humor Scale

As shown in Table 5.3, the Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin (KMO) value for the leadership-friendly humor scale is 0.950, significantly exceeding the threshold of 0.7. Additionally, the Bartlett’s test of sphericity yielded

an approximate chi-square value of 1991.880, with a significance level (P) below 0.001. These results confirm that the scale is structurally suitable for factor analysis.

Table 5.3 KMO and Bartlett’s Sphericity Test of Leadership-Friendly Humor Scale

KMO Sampling Adequacy 0.950

Approx. Chi-Square 1991.880

Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity Degrees of Freedom 28

Significance Level .000

From Table 5.2, all variables exhibit Cronbach’s α coefficients above 0.8, demonstrating outstanding reliability and

internal consistency. Hence, the collected data passed the reliability test and can be deemed stable and dependable.

(2) Validity Analysis ofEmployees ’ Emotional Commitment Scale

Table 5.4 illustrates that the KMO value for the employees’ emotional commitment scale is 0.936, surpassing the standard of 0.8. The Bartlett’s test yielded

a chi-square value of 1896.118, with a P-value below 0.001, indicating significant results. These findings support the structural validity of the scale for factor analysis.

Table 5.4 KMO and Bartlett Sphericity Test of Supervisor's Emotional Commitment Scale

KMO Sampling Adequacy 0.936

Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity Approx. Chi-Square 1896.118

Degrees of Freedom 28

Significance Level .000

(3) Validity Analysis of Proactive Behavior Scale

As shown in Table 5.5, the proactive behavior scale has a KMO value of 0.899, exceeding the acceptable standard of 0.8.

The Bartlett’s test yielded a chi-square value of 1164.884, with a significance level below 0.001, further confirming its structural validity for factor analysis.

Table 5.5 KMO and Bartlett’s Sphericity Test of Proactive Behavior Scale

KMO Sampling Adequacy 0.884

Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity Approx. Chi-Square 1164.884

Degrees of Freedom 21

Significance Level .000

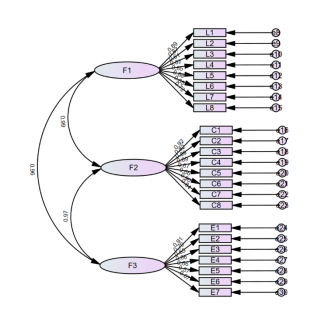

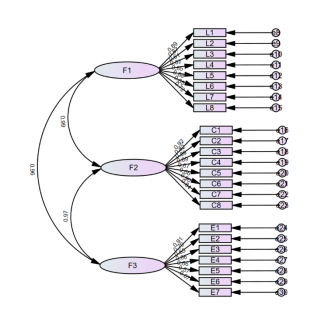

5.3 Confirmatory Factor Analysis

The purpose of validity testing is to verify whether the measurement scales selected for the study accurately measure the levels of the variables involved in the research questions, thereby reflecting the content validity of the constructs. The scales referenced in this study have been well-validated and widely applied in prior empirical research. The content of the items aligns closely with the

phenomena being measured. Thus, this study employs confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to conduct a detailed examination of both convergent and discriminant validity.

1. Construct Validity

As shown in Table 5.6, the model exhibits a good fit (CMIN/DF = 2.362, which is less than 3,

indicating an ideal fit; RMSEA = 0.067; NFI = 0.920, RFI = 0.910, IFI = 0.952, TLI = 0.946, and CFI = 0.952, all exceeding 0.9).

Table 5.6 Overall Fit Coefficient

CMIN/DF RMSEA NFI RFI IFI TLI CFI

2.362 0.067 0.920 0.910 0.952 0.946 0.952

According to Table 5.7, the factor loadings for all items corresponding to the three variables—leader affiliative humor, employee affective commitment, and employee proactive behavior—exceed the threshold of 0.5, indicating strong representativeness between each latent variable and its respective items. Additionally, the average variance extracted (AVE) values for

all latent variables exceed 0.5, and their composite reliability (CR) values are all above 0.8. These data collectively confirm a satisfactory level of convergent validity.

Figure 5.1 Three-Factor Structural Equation Model Diagram

Table 5.7 Convergent Validity

Path Estimate AVE CR

L1 ← Leader Affiliative Humor 0.888

L2 ← Leader Affiliative Humor 0.866

L3 ← Leader Affiliative Humor 0.614

L4 ← Leader Affiliative Humor L5 ← Leader Affiliative Humor 0.871 0.849 0.6771 0.9431

L6 ← Leader Affiliative Humor 0.883

L7 ← Leader Affiliative Humor 0.854

L8 ← Leader Affiliative Humor 0.716

C1 ← Employee Affective Commitment 0.919

C2 ← Employee Affective Commitment 0.815

C3 ← Employee Affective Commitment 0.886

C4 ← Employee Affective Commitment C5 ← Employee Affective Commitment 0.693 0.671 0.6467 0.9352

C6 ← Employee Affective Commitment 0.663

C7 ← Employee Affective Commitment 0.896

C8 ← Employee Affective Commitment 0.841

E1 ← Employee Proactive Behavior 0.911

E2 ← Employee Proactive Behavior 0.791

E3 ← Employee Proactive Behavior 0.650

E4 ← Employee Proactive Behavior 0.859 0.5474 0.892

E5 ← Employee Proactive Behavior 0.662

E6 ← Employee Proactive Behavior 0.570

E7 ← Employee Proactive Behavior 0.673

5.4 Correlation Analysis

Using SPSS 27.0, a Pearson correlation analysis was conducted to preliminarily test and clarify the relationships between variables.

The detailed results are presented in Table 5.8:

There is a significant positive correlation between leader affiliative humor and employee affective commitment (r = 0.939, p < 0.01).

Leader affiliative humor is significantly positively correlated with employee proactive behavior (r = 0.872, p < 0.01).

Employee affective commitment is significantly positively correlated with employee proactive behavior (r = 0.882, p < 0.01).

These findings provide a solid foundation for testing the research hypotheses.

e 5.8 Descriptive Statistics of Variables and Correlation Coefficient Analysis

Variable Mean SD Leader Affiliative Humor Employee Affective Commitment Employee Proactive Behavior

Leader Affiliative Humor

Employee Affective Commitment

Employee Proactive Behavior 3.27 3.12 3.08 1.03 0.93 0.83 1

0.939** 0.872** 1

0.882**

1

*Note: **p < 0.01, p < 0.05

The results of the correlation analysis provide preliminary evidence for Hypotheses 1, 2, 3, and 4.

5.5 Mediating Effect Analysis

This study controlled for demographic variables such as employee gender, age, and tenure with the leader and performed hierarchical regression analysis using SPSS 27.0, as well as validation using Process 4.1. First, Model 1 (M1) was constructed with employee proactive behavior as the dependent variable and leader affiliative humor as the independent variable, controlling for gender, age, and tenure. Second, Model 2 (M2) was created by including employee affective commitment as a mediating variable.

Third, Model 3 (M3) analyzed the effect of leader affiliative humor on employee affective commitment. The regression analysis results are presented in Table 5.9.

To explore the mechanism underlying the positive impact of leader affiliative humor on employee proactive behavior, this study incorporated employee affective commitment as a mediating variable into a structural equation model. The mediation

effect was tested using Model 4 of the Process macro in SPSS, following Hayes' Bootstrap method. The path coefficients among the three variables are depicted in Figure 5.2.

Figure 5.2 Path Factor Diagram

According to Table 5.9, the bootstrap 95% confidence intervals for the mediating effects of leader affiliative humor on employee proactive behavior and employee affective commitment do not include zero. This indicates that leader affiliative humor not only directly influences employee proactive behavior but also exerts an indirect influence through employee affective

commitment as a mediating variable. The direct effect (0.64) and mediating effect (0.21) account for 75.30% and 24.70% of the total effect, respectively.

Table 5.9 Breakdown of Total, Direct, and Mediating Effects

Effect Effect Value Boot SE Boot CI Lower Limit Boot CI Upper Limit Relative Effect %

Mediating Effect 0.21 0.04 0.13 0.30 24.70%

Direct Effect 0.64 0.03 0.57 0.70 75.30%

Total Effect 0.85 0.02 0.81 0.88

Note: The indirect effect represents Leader Affiliative Humor → Employee Affective Commitment → Employee Proactive Behavior.

The direct effect represents Leader Affiliative Humor → Employee Proactive Behavior.

6 Conclusion and Outlook

6.1 Research Findings

This study explored the mediating role of employees’ affective commitment in

the relationship between affiliative humor exhibited by leaders and employees’ proactive behavior. All proposed hypotheses were supported, as detailed in Table 6.1:

Table 6.1 Summary of Hypothesis Testing

Hypotheses Results

H1 Affiliative humor by leaders positively predicts employees' proactive behavior. Supported

H2 Affiliative humor by leaders positively predicts employees' affective commitment. Supported

H3 Employees' affective commitment positively predicts their proactive behavior. Supported

H4 Employees' affective commitment mediates the relationship between affiliative humor by leaders and employees' proactive behavior. Supported

(1) The Positive Predictive Role ofAffiliative Humor in Employees ’ Proactive Behavior

The findings indicate that leaders’ affiliative humor positively predicts employees’ proactive behavior within the organization. Employees who perceive affiliative humor from their leaders tend to develop a more positive perspective on their relationship with the leader, which motivates them to put in greater effort and exhibit proactive behaviors. Such behaviors not only enhance work performance and reduce managerial burdens but also foster actions that benefit the organization, forming a virtuous cycle of reciprocity. Grounded in social exchange theory and the principle of reciprocity,

employees influenced by affiliative humor develop a heightened sense of belonging and ownership within the organization, thereby increasing their proactive engagement in work.

(2) The Positive Predictive Role ofAffiliative Humor in Employees ’ Affective Commitment

Affiliative humor exhibited by leaders fosters employees' emotional attachment to their supervisors. Based on Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, humans naturally seek social connection and psychological safety. Leaders’ affiliative humor creates a positive and inclusive interactional atmosphere, allowing employees to identify themselves as integral members of their supervisors’ teams. This sense of identity motivates employees to maintain harmonious relationships with their supervisors,

reducing perceived risks such as dismissal and enhancing their sense of social security. This, in turn, strengthens employees’ affective commitment to their supervisors.

(3) The Positive Predictive Role ofAffective Commitment in Employees ’ Proactive Behavior

Employees' proactive behavior is positively driven by their affective commitment to their supervisors. According to Mayo's human relations theory, employees are "social beings" whose workplace behavior is significantly influenced by their interpersonal relationships, particularly with their supervisors. High affective commitment improves employees’ morale and enthusiasm, leading to higher productivity. Thus, affective commitment serves

as a critical predictor of proactive behavior, with employees displaying stronger emotional attachment more likely to engage in proactive and constructive work behavior.

(4) The Mediating Role ofAffective Commitment

This study confirmed the mediating role of employees’ affective commitment in the relationship between affiliative humor by leaders and employees’ proactive behavior. Employees who perceive stronger affiliative humor from their leaders demonstrate higher affective commitment toward their supervisors, which in turn drives proactive workplace behaviors. In the context of traditional Chinese culture, leaders are often likened to "family heads" in organizations. Their management style and behaviors significantly influence employees’ work attitudes and emotional dispositions, which then shape work

behaviors. This study not only elucidates the indirect mechanism through which affiliative humor impacts proactive behavior but also contributes a novel theoretical perspective to research on leader-employee dynamics within the Chinese cultural context.

6.2 Implications for Managerial Practice

(1) Recognizing the Value ofLeaders ’ Affiliative Humor

Employees’ proactive behavior is a valuable asset for organizations. Understanding and leveraging the mechanisms that foster such behavior is crucial. This study highlights the critical role of affiliative humor in stimulating employees’ proactive actions. Leaders’ humor creates an open and positive communication environment while strengthening emotional bonds between employees and the organization.

Organizations seeking to foster innovation and change should recognize and harness the importance of affiliative humor as part of leadership strategies.

(2) Cultivating Employees ’ Affective Commitment

Employees’ attitudes and behaviors are significantly influenced by their emotional attachment to their supervisors. This

study shows that employees with higher affective commitment are more likely to exhibit proactive behavior, resulting in superior performance. According to the reciprocity principle, employees often repay their leaders’ care and support through excellent job performance or voluntary organizational contributions. Thus, organizations should understand

the pivotal role of supervisors in fostering trust and closeness with employees, creating a harmonious work environment to encourage proactive behavior.

(3) Training Leaders in Affiliative Humor

Affiliative humor not only strengthens leader-subordinate relationships but also fosters an environment conducive to emotional bonding between employees and the organization. This leadership style enhances employees’ organizational commitment and work engagement, driving higher contributions to organizational goals. Therefore, organizations should prioritize training programs for leaders to develop affiliative humor.

By updating managerial practices and deepening leaders’ understanding of the value of humor in leadership, organizations can create more cohesive and efficient work environments.

6.3 Limitations and Future Directions

(1) Adaptation ofMeasurement Scales

This study primarily employed scales translated from mature Western instruments to measure variables. Although these scales have been validated for reliability and validity, their applicability to Chinese organizations remains a question worthy of exploration.

Future studies could examine the cultural relevance and effectiveness of these scales in the Chinese context to ensure the accuracy and reliability of research findings.

(2) Data Collection via Self-report Questionnaires

Data collection relied primarily on self-reported questionnaires. While effective, this method has limitations. Employees may readily recognize affiliative humor, especially humor involving others. However, evaluations of the same leader can vary among observers. Leaders may also exhibit different humor styles at work and in personal life, with employees predominantly exposed to the former. To better understand how affiliative

humor influences proactive behavior, future research could incorporate both employee evaluations and leaders’ self-assessments to obtain more comprehensive and objective data.

(3) Enhancing Leaders ’ Affiliative Humor

This study focused on the effects of affiliative humor but did not delve into strategies for enhancing leaders’ humor. As humor is a learnable trait, multiple factors, such as gender, job performance, and hierarchical position, may influence its development. Exploring these factors’ effects could deepen our understanding of the nature of affiliative humor. Insights gained could

guide leader selection and training processes, enabling organizations to shape leaders’ humor styles from the outset and foster harmonious and productive work environments.

7. Insights from Cana’s practice

The following practices illustrate how Canadian organizations leverage leadership traits such as affinity humor and emotional commitment to encourage proactive employee behavior:

(1)Use of Humor to Foster Psychological Safety

Canadian leaders often use humor to create a workplace environment where employees feel safe to express themselves and take initiative. For instance, leaders in companies like Shopify and TELUS integrate lighthearted communication to reduce stress and build

rapport with employees. This aligns with findings that affinity humor from leaders can strengthen bonds and motivate employees to go above and beyond their responsibilities.

Application in China: Leaders in Chinese companies can adopt humor as a tool to break hierarchical barriers, foster trust, and encourage proactive behavior.

(2) Leader Emotional Commitment as a Catalyst

Canadian leaders actively demonstrate emotional commitment to their teams, which serves as a powerful motivator for employees. Emotional commitment is reflected in consistent recognition, genuine interest in employee well-being, and personalized support. For example, the Employee

Assistance Programs widely adopted in Canada signal emotional investment in employees’ personal and professional growth, leading to greater engagement and initiative-taking.

Application in China: Managers can demonstrate emotional commitment by

recognizing individual contributions, showing empathy during challenges, and providing support for employees’ career development to drive proactive behavior.

(3)Building Trust and Transparency Through Leadership Style

Canadian organizations value transparent and trust-building leadership styles that empower employees. Leaders are encouraged to maintain open communication,

actively listen to employees’ ideas, and involve them in decision-making processes. Such practices foster a sense of ownership and encourage employees to take proactive actions.

Application in China: Chinese leaders can build trust and transparency by

creating regular forums for open dialogue, empowering employees with decision-making authority, and acknowledging their contributions to organizational success.

(4)Cultivating an Inclusive and Engaging Workplace Culture

Canadian companies are known for cultivating inclusive and engaging workplaces where employees feel a sense of belonging. Leaders play a key role in maintaining this culture

by ensuring that humor and interactions are inclusive and culturally sensitive, which strengthens emotional bonds and encourages employees to exhibit proactive behaviors.

Application in China: Leaders can develop training on inclusivity and

cultural sensitivity, ensuring that humor and interactions resonate positively across diverse employee groups, thereby promoting proactive behaviors.

(5)Formalizing Leadership Development Programs

In Canada, leadership training programs often emphasize the development of emotional intelligence, including humor and empathy, as tools for effective management. Programs such as those offered by the Canadian Centre for Leadership

and Development train leaders to balance professional authority with approachable, engaging communication styles that enhance team dynamics and employee initiative.

Application in China: Chinese enterprises can formalize leadership training programs that focus on the use of humor, empathy,

and emotional intelligence to strengthen leaders' ability to inspire proactive behaviors among employees.

8.Recommendations for Chinese Enterprises

Drawing from Canadian workplace practices, the following recommendations can help Chinese organizations leverage leaders’ affinity humor and emotional commitment to foster proactive employee behavior: (1) Integrate Humor into Leadership Training: Train leaders to use humor appropriately to build rapport and create a psychologically safe environment that encourages proactive behavior.(2) Show Genuine Emotional Commitment: Encourage leaders to demonstrate genuine concern for employees’ well-being and career development, reinforcing trust and emotional bonds.(3) Promote Open Communication: Develop channels for transparent and open communication where employees feel their voices are heard and valued.(4) Create Inclusive Leadership Practices: Ensure that humor and interpersonal interactions are inclusive and culturally appropriate to strengthen team cohesion and engagement.(5)Adopt

Leadership Development Programs: Implement formal training programs focusing on emotional intelligence, humor, and empathy as tools for inspiring proactive employee behavior.

1.

Allen, N. J., & Meyer, J. P. (1990). The measurement and antecedents of affective,

continuance and normative commitment to the organization. Journal of Occupational Psychology, 63(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1990.tb00506.x

2.

Askew, K., Taing, M. U., & Johnson, R. E. (2013). The effects of

commitment to multiple foci: An analysis of relative influence and interactions. Human Performance, 26(3), 171-190. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2013.800412

3.

Baek, H., Han, K., & Ryu, E. (2019). Authentic leadership,

job satisfaction and organizational commitment: The moderating effect of nurse tenure. Journal of Nursing Management, 27(8), 1655-1663. https://doi.org/10.1111/jonm.12789

4.

Becker, T. E. (1992). Foci and bases of commitment: Are they distinctions worth making? Academy of Management Journal, 35(1), 232-244.

https://doi.org/10.5465/256476

5.

Becker, T. E., Billings, R. S., Eveleth, D. M., et al. (1996).

Foci and bases of employee commitment: Implications for job performance. Academy of Management Journal, 39(2), 464-482. https://doi.org/10.5465/256657

6.

Cai, Z., Parker, S. K., Chen, Z., et al. (2019). How does the social

context fuel the proactive fire? A multilevel review and theoretical synthesis. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 40(2), 209-230. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.2343

7.

Clugston, M., Howell, J. P., & Dorfman, P. W. (2000).

Does cultural socialization predict multiple bases and foci of commitment? Journal of Management, 26(1), 5-30. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630002600102

8.

Cooper, C. D., Kong, D. T., & Crossley, C. D. (2018). Leader humor

as an interpersonal resource: Integrating three theoretical perspectives. Academy of Management Journal, 61(2), 769-796. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2015.0295

9.

Crant, J. M. (2000). Proactive behavior in organizations. Journal of Management, 26(3), 435-462. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630002600304

10.

Decker, W. H., Yao, H., & Calo, T. J. (2011). Humor, gender, and perceived leader. SAM Advanced Management Journal, 76(2), 52-63.

11.

Du, H., Zhu, Q., & Liu, C. (2019). The impact mechanism of workplace negative gossip on proactive behavior: A moderated mediation model. Management Review, 31(2), 190-199.

12.

Frese, M., Fay, D., Hilburger, T., et al. (1997). The concept of personal initiative: Operationalization, reliability and

validity in two German samples. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 70(2), 139-161. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.1997.tb00639.x

13.

Gao, J., Wen, Z., Wang, Y., et al. (2019). The impact of leader humor styles on team learning. Psychological Science, 42(4), 913-919.

14.

Kim, S., & Ishikawa, J. (2021). Contrasting effects of “external” worker’s proactive behavior

on their turnover intention: A moderated mediation model. Behavioral Sciences, 11(5), 70. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs11050070

15.

Kim, T. Y., Lee, D. R., & Wong, N. Y. S. (2016). Supervisor humor and employee outcomes:

The role of social distance and affective trust in supervisor. Journal of Business and Psychology, 31, 125-139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10869-015-9414-0

16.

Landry, G., & Vandenberghe, C. (2009). Role of commitment to the supervisor, leader-member exchange,

and supervisor-based self-esteem in employee-supervisor conflicts. The Journal of Social Psychology, 149(1), 5-28. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224540903365409

17.

Marinova, S. V., Peng, C., Lorinkova, N., et al. (2015).

Change-oriented behavior: A meta-analysis of individual and job design predictors. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 88, 104-120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2015.02.001

18.

Martin, R. A., Puhlik-Doris, P., Larsen, G., et al. (2003). Individual differences in uses of humor and their relation

to psychological well-being: Development of the Humor Styles Questionnaire. Journal of Research in Personality, 37(1), 48-75. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00046-6

19.

Matsuo, M. (2022).

Reflection on success in promoting authenticity and proactive behavior: A two-wave study. Current Psychology, 41(12), 8793-8801. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03198-z

20.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1991).

A three-component conceptualization of organizational commitment. Human Resource Management Review, 1(1), 61-89. https://doi.org/10.1016/1053-4822(91)90011-Z

21.

Meyers, M. C. (2020). The neglected role of talent

proactivity: Integrating proactive behavior into talent-management theorizing. Human Resource Management Review, 30(2), 100703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2019.100703

22.

Ohly, S., Göritz, A. S., & Schmitt,

A. (2017). The power of routinized task behavior for energy at work. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 103, 132-142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.08.001

23.

O'Reilly, C. A., & Chatman, J. (1986). Organizational commitment and psychological attachment: The effects of compliance,

identification, and internalization on prosocial behavior. Journal of Applied Psychology, 71(3), 492-499. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.71.3.492

24.

Parker, S. K., Williams, H. M., & Turner,

N. (2006). Modeling the antecedents of proactive behavior at work. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91(3), 636-652. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.91.3.636

25.

Priest, R. F., & Swain, J. E.

(2002). Humor and its implications for leadership effectiveness. Journal of Leadership & Organizational Studies, 9(3), 35-52. https://doi.org/10.1177/107179190200900303

26.

Pundt, A. (2015). The relationship between humorous leadership and innovative behavior.

Journal of Managerial Psychology, 30(8), 878-893. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-02-2014-0081

27.

Pundt, A., & Herrmann, F. (2015). Affiliative and aggressive humour in leadership

and their relationship to leader–member exchange. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 88(1), 108-125. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12074

28.

Shi, G., Mao, S., & Wang, K. (2017).

The mechanism of humorous leadership on employee creativity: A perspective based on social exchange theory. China Human Resource Development, 34(11), 17-31.

29.

Stamper, C. L., & Masterson, S. S. (2002).

Insider or outsider? How employee perceptions of insider status affect their work behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23(8), 875-894. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.176

30.

Stinglhamber, F., & Vandenberghe, C. (2003). Organizations and

supervisors as sources of support and targets of commitment: A longitudinal study. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 24(3), 251-270. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.198

31.

Vandenberghe, C., Bentein, K., & Stinglhamber, F. (2004). Affective commitment

to the organization, supervisor, and work group: Antecedents and outcomes. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 64(1), 47-71. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0001-8791(03)00031-8

32.

Wang, R., & Lv, L. (2021). The impact of leader affiliative humor on team effectiveness in the context of collectivist culture in China. Business and Management, 33(12), 142-150.

33.

Wang, R., & Lv, L. (2021). The impact of leader affiliative humor on team effectiveness in the context of collectivist culture in China. Business and Management, 33(12), 142-150.

34.

Wang, Y. Q. (2012). The role and mechanism of organizational justice in employee deviant behavior (Doctoral dissertation). Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan.

35.

Weng, J., Lin, Y., & Hu, F. P. (2018). Team empowerment and collective

turnover intention of members: The mediating role of affective commitment. Applied Psychology, 24(4), 259-268+216.

36.

Wu, C. H., & Parker, S. K. (2017). The role of leader support in

facilitating proactive work behavior: A perspective from attachment theory. Journal of Management, 43(4), 1025-1049. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314525203

37.

Wu, X., Kwan, H. K., Wu, L. Z., et al. (2018). The effect of workplace negative gossip

on employee proactive behavior in China: The moderating role of traditionality. Journal of Business Ethics, 148, 801-815. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3069-7

38.

Xu, Q., Zhang, G., & Chan, A. (2019). Abusive supervision and subordinate proactive behavior:

Joint moderating roles of organizational identification and positive affectivity. Journal of Business Ethics, 157, 829-843. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3690-1

39.

Yan, J., Fan, Y., & Zhang, X. (2016). Compliant and challenge-oriented organizational citizenship behavior:

Based on the dual paths of emotional experience and rational cognition. Journal of Management Engineering, 30(3), 63-71. https://doi.org/10.13587/j.cnki.jieem.2016.03.008

40.

Yao, L., & Chen, Y. (2015). Empirical study on

how organizational career management enhances employees' emotional attachment and commitment to the organization. Modern Management Science, 2015(4), 106-108+117.

41.

Yin, K., Liu, Y. R., & Song, L. L. (2016). Leader-friendly relationship management (LRM) and employee

affective commitment: The mediating and moderating role of LMX. Journal of Management Engineering, 30(4), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.13587/j.cnki.jieem.2016.04.001

42.

Zhang, Y., Duan, J., Wang, F., et al. (2022).

"Near vermilion, one gets stained": How colleague proactive behavior stimulates employee motivation and performance. Acta Psychologica Sinica, 54(5), 516.

43.

Zhao, H., & Long, L. (2016). Personal-environment fit, self-determination,

and emotional commitment based on a multi-theoretical perspective. Journal of Management, 13(6), 836-846. https://doi.org/10.13587/j.cnki.jieem.2016.06.008

44.

Zheng, B. X. (2006). Differentiated order pattern and Chinese organizational behavior. Chinese Journal of Social Psychology, 2, 1-52.

45.

Zhou, H., Long, L., & Wang, Y. Q. (2016). Overall fairness, emotional commitment, and employee

deviant behavior: An analysis based on a multi-object perspective. Management Review, 28(11), 162-169. https://doi.org/10.14120/j.cnki.cn11-5057/f.2016.11.015

Figure 3.1 Theoretical Model

Figure 3.1 Theoretical Model

Figure 5.1 Three-Factor Structural Equation Model Diagram

Figure 5.1 Three-Factor Structural Equation Model Diagram

Figure 5.2 Path Factor Diagram

Figure 5.2 Path Factor Diagram